Scientists Discover True Identity of Ancient Sea-Lizard

Researchers identified a prehistoric marine reptile found in 1935 as a thalattosaur, not a choristodere, using CT scans and a new specimen. Reconstruction of Pachystropheus rhaeticus, figured alongside a hybodont shark feeding on a Birgeria fish. Credit: James Ormiston

Scientists have reclassified a prehistoric marine reptile discovered in 1935 as one of the last thalattosaurs, not an early choristodere, after new findings and detailed imaging.

The true identity of a local prehistoric marine reptile has been uncovered after experts determined that some of its remains actually belonged to fish.

Researchers from the University of Bristol and the University of Southampton have established that bones found in Triassic rocks in 1935 are from one of the final thalattosaurs, a large sea-lizard that behaved like an otter.

For years it was assumed the ancient animal was one of the first choristoderes, another group of crocodile-like marine reptiles. However, in the study, published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, the team examined the original name-bearing specimen from 1935. They compared this to a remarkable new specimen of Pachystropheus, known as ‘Annie’, that contains hundreds of bones from several individuals, as well as evidence of sharks, bony fish, and even terrestrial dinosaurs.

Advanced Techniques and Characteristics

Jacob Quinn, who is studying for his Masters in Palaeobiology at Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences, traveled with the two specimens to Southampton where they were CT scanned, producing stacks of X-rays through the blocks that allowed him to reconstruct a complete 3D model of everything buried in the blocks.

“Thalattosaurs existed throughout the Triassic,” explained Jacob. “Some of them reached four meters (13 feet) in length and would have been the terrors of the seas. But our Pachystropheus was only a meter long, and half of that was its long tail. It had a long neck too, a small head the size of a matchbox, which we hadn’t found, and four paddles. If it was like its relatives, it would have had lots of sharp little teeth, ideal for snatching fish and other small, wriggly prey.”

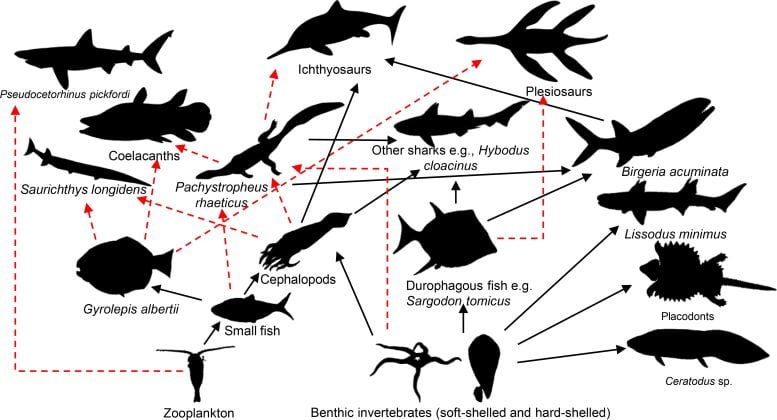

Rhaetian (205 million years ago) food web of the Bristol archipelago containing Pachystropheus rhaeticus. The arrows indicate who eats who – red and black means inferred, and blue arrows are based on based upon ecology and fossil associations observed during this study. Credit: Jacob Quinn

“Previously Pachystropheus had been identified as the first of the choristoderes, another group of crocodile-like marine reptiles, and it was treated as very important because it was the oldest,” said Professor Mike Benton, one of Jacob’s supervisors. “Jacob was able to show that some of the bones actually came from fishes, and the others that really belonged to Pachystropheus show it was actually a small thalattosaur. So, from being regarded as the first of the choristoderes, it’s now identified as the last of the thalattosaurs.”

Discovery and Reconstruction Efforts

Evangelos R. Matheau-Raven of Peterborough discovered Annie while on holiday in Somerset in 2018, and he then painstakingly pieced it back together and cleaned it to expose the bones in his spare time. He said: “I spotted parts of a fallen rock on the beach about 10m from the base of the cliff. I was thrilled as their exposed surfaces showed some fossil bones. It wasn’t until a few days later that I could see that the pieces collected two days apart fitted together. After a few weeks of preparation, we could see that something special was emerging. The specimen took me some 350 hours and about a year to complete.”

Evangelos R. Matheau-Raven during the preparation of ‘Annie’. Credit: Evangelos R. Matheau-Raven/Andrea Matheau-Raven

“Pachystropheus probably lived the life of a modern-day otter, eating small fish or invertebrates such as shrimps,” says Dr David Whiteside, another supervisor. “These slender reptiles had long necks, a tail flattened for swimming, and remarkably robust forelimbs for a marine animal, which suggests Pachystropheus may have come onto land to feed or to avoid predators. At the time, the Bristol area, and indeed much of Europe, was shallow seas, and these animals may have lived in a large colony in the warm, shallow waters surrounding the island archipelago.”

Annie will now be housed in the Bristol Museum & Art Gallery for further study.

“We are very happy that this incredible fossil is now part of the collection at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, thanks to the kind assistance from the Friends of Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives. We are excited to be able to share the story of this new fossil and all the work the team have has achieved with visitors to the museum,” says Bristol Museum & Art Gallery geology curator, Deborah Hutchinson.

Reference: “The relationships and paleoecology of Pachystropheus rhaeticus, an enigmatic latest Triassic marine reptile (Diapsida: Thalattosauria)” by Jacob G. Quinn, Evangelos R. Matheau-Raven, David I. Whiteside, John E. A. Marshall, Deborah J. Hutchinson and Michael J. Benton, 4 June 2024, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2024.2350408